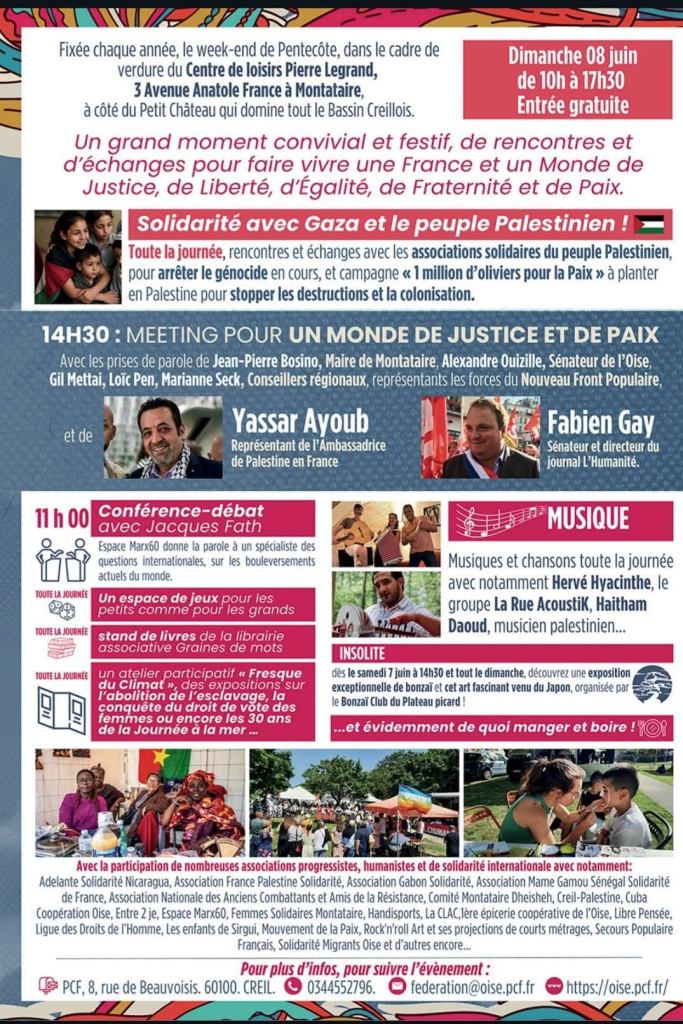

Below is the text of my introductory speech at a conference-debate organised on 8 June in Montataire by Espace Marx60, as part of a PCF celebration on the theme of a world of peace and solidarity.

One theory dominates today, that of a ‘return’ to war… In truth, wars have never stopped… But today we are talking about what is known as high-intensity warfare (with a high level of destruction and lethality…), inter-state warfare involving the major powers. This is what we will be discussing in particular.

Let me explain how I see it.

The current international order can be understood in terms of two key moments.

The first was the establishment in 1945 of what is known as the liberal international order, with the creation of the United Nations. This was an institutionalised, standardised order. The Western powers, and the United States in particular, played a major role in its foundation.

The second crucial moment was the collapse of the USSR and the Soviet world. The end of the Cold War. This moment ushered in a new era of disintegration of the order established in 1945. It was a decisive break with serious consequences for European and world history.

This leads me to two observations.

Firstly, the Western powers, led by the United States, treated the failure of Sovietism as a victory for the Western powers. In this new context, NATO and the EU chose to extend their zones of influence and strategic pre-eminence to the borders of a then very weakened Russia. This process was never accepted by the Russians… even though Yeltsin adopted attitudes that were particularly favourable to the United States.

Secondly, the failure of the so-called Eastern European regimes holds lessons. Lessons about the mode of development, about democracy and political power, about what we call socialism… Obviously. But it also teaches lessons about power, because the collapse of the USSR also meant the severe and probably lasting weakening of a major world power that, together with the United States, helped to structure the international order during the Cold War. Russia is no longer in a position to do this today.

This should – I would emphasise – help to put into perspective what is currently being presented as the Russian threat to Europe (I will say more about this later).

As for the European states, we are told that they have lost their sense of tragedy… that is to say, their awareness of the possibility, even the probability, of war. Europeans have therefore been unwilling to face reality, the Russian threat and the Chinese threat in particular. They are therefore unprepared for war. They must now prepare themselves because, we are told, war is already here. It is a ‘hybrid war’… one waged with specific means and methods of interference, destabilisation, economic and ideological pressure… But this is not the same thing as war itself.

Europeans (states and peoples) must therefore prepare themselves on all fronts: military, political, financial, industrial, psychological… right down to the war economy.

What is the real problem?

It is clear that the dangers of a major war, also known as a major conflict, are high. There is already the war in Ukraine (with its limitations and dangers), the Israeli war against the Palestinian people (and its regional aspects), and in Asia, the risk of a Sino-American war, which would certainly result in a very intense confrontation. We have also seen a worrying Indo-Pakistani confrontation between two countries with nuclear weapons. The risks are real in a context of tensions and an arms race…

However, except in Palestine and the Middle East, where Israeli strategy and the ongoing genocidal process raise particular questions, these conflicts appear to be relatively under control. While the worst is never certain, anything is possible. No one can predict the consequences of a misjudgment, an accident or an uncontrolled escalation. This is all the more true given that the rules and practices of what is known as collective security, as defined by the UN, are being set aside, along with diplomacy, in an international context dominated by power politics and force.

This touches on something essential: the contradiction between principles and practices. On the one hand, there are the rules and values defined by international law as a whole and by the United Nations (with the Charter); on the other, there are the forces at work in practice: power, forceful policies, unilateralism and imperialist strategies.

This issue must be raised because standards must be respected in order to pacify international relations and, above all, to contribute to mutual security and cooperation.

It is because these norms and the law are no longer respected, and are even rejected, that tensions and the risk of war are increasing. There are virtually no rules or collective mechanisms left that are respected, or at least sufficient to curb and tame the logic of power.

This process of disintegration of multilateralism, collective action and the law must be seen in parallel with the neoliberal devastation of societies and the undermining of democracy, political, judicial and social institutions, and the public sector. This has been expressed, to varying degrees, by social movements such as Occupy Wall Street in the United States, the Arab Spring, the yellow vests in France, and many other more structured social and trade union struggles.

There is therefore no process of escalation towards war that Europeans would not have wanted to see. The situation is not that simple. First, there are strategic rivalries and power struggles that continue to contribute to a profound deterioration in international relations, the emergence of desires for revenge, and the worsening of injustices, inequalities and unmet basic needs. The processes are therefore much more complex than is often acknowledged.

Let me give you a current example. It is often said that Vladimir Putin is ‘solely responsible’ for the war in Ukraine. It is true that Putin’s regime took responsibility for starting the war. It did so in violation of international law, the principles and purposes of the United Nations Charter, and even Russia’s own commitments made in 1994 in the three Budapest memoranda it signed, which provided guarantees of security and territorial integrity to Ukraine.

In terms of international law, Russia’s responsibility is therefore clear. But we must also ask a political question: how did we get here? We cannot reflect on conflicts and wars without considering the strategies implemented and the geopolitical context. We cannot escape history and the context of events. And this is probably why the idea and even the word “contextualisation” have been banned from public and media debate in order to avoid any reasoned explanation or questioning of Western theories.

I’m explaining things a little because what happened at the end of the Cold War is fundamental to understanding what followed. The collapse of the USSR and the system of alliances linked to it was a historic turning point, a major strategic shift in global geopolitics.

Instead of seizing this crucial moment of change to help establish a new international order and a new security order in Europe, the United States, together with the Europeans, deliberately interpreted the end of the USSR as a historic defeat for Russia. They therefore decided to expand NATO’s strategic space to Russia’s borders. This was logically seen by Moscow as a weakening of its security and a direct threat. For the Western powers, it was a form of opportunistic escalation. At the time, there were no serious negotiations with Russia on new international security conditions and a necessary new order.

Washington thus claimed a so-called ‘victory’ as a gain for American power. But as soon as he came to power (in 2000), Putin has constantly sought to rebuild Russian power, particularly in military terms, by seeking to regain some of the territories and grandeur lost. Some have interpreted this choice as an ambition to rebuild the vast empire of the Tsars or the former Soviet power. This is far from the case. Even the conquest of Ukraine remains a difficult ambition for Moscow to achieve.

The war in Ukraine is, in essence and in its origins, a NATO/Russia war. It is also the result of choices… that were not made. Let me explain.

When decisive events and ruptures shake history, it becomes necessary to establish new rules for coexistence and security, a new order. This is what was done in 1945, and at other times in history… In 1991, the Western powers did not want this. It is true that the American strategy has been explicitly marked, permanently and over the long term, since the Second World War, as one of containment and then strategic repression of the USSR, and later of Russia. In 1991, when the USSR collapsed, Clinton, then President of the United States, did not deviate from this fundamental strategic orientation of the United States as a global power.

In the same vein, I would point out that US strategy has also long been one of explicitly refusing to allow the emergence of a rival power or equal competitor, which explains the current conflict with China. In this regard, Washington has not yet won the day…

This leads me to recall something that we tend to pretend to forget, even though it is crucial. Security is necessarily a reciprocal process. It requires mutual trust, cooperation based on shared interests and consultation. Contrary to what the Western powers claim, it cannot be said that a state is completely free to join a political and military alliance such as NATO by virtue of a non-negotiable sovereign choice. The UN Charter establishes precisely the opposite. It sets out the principles and practices of collective security. No one is safe if others, including adversaries, are not. In international security, collective responsibility must prevail. There can be no security or peace through force and the unilateral expression of power… This mainly leads to escalation and risks.

This essential principle of collective security is now being flouted by Putin’s decision to wage war in Ukraine. Just as it was flouted yesterday by the American wars decided upon in 2001 by George W. Bush. We can see that Russia is hardly in a position to achieve a real victory in Ukraine, just as failure was the end result of the hubris and excesses of the United States in its quest for a Greater Middle East of liberalism, free trade and the Western model under American leadership. What is at stake, therefore, is first and foremost the logic of power that has created deadlocks, major crises and this dangerous deterioration in international relations for nearly 35 years.

This deterioration is profound. Over the years, since the end of the Cold War, there has been a process of gradual decomposition of the international order. This has been accompanied by a worrying disregard for international law and multilateralism. It has seen the dismantling of what is known as the collective security architecture, comprising the treaties signed to establish arms limitations and controls, and the disarmament treaties.

Let me give you an example. If the New START Treaty (signed in 2010) on strategic nuclear weapons is not extended before its expiry on 5 February 2026, there will be no valid and applicable agreement on strategic nuclear weapons. This is alarming for international security.

But why is this process of disintegration happening?

In the context of the end of the Cold War, we are witnessing a geopolitical shift: a proliferation of powerful actors. The emergence of China as a major competitor to the United States. An increase in conflicts over resources, technologies, markets, spheres of influence and, of course, the hierarchy of powers. In this redistribution of power and competition of interests, the practices and rules of collective security are becoming obstacles. Force prevails over law. The battle for hegemony is raging. The United States does not want a competitor on its level, such as China. Europe is struggling to exist in this confrontation between giants, which also involves other new powers, notably Brazil, India, Indonesia and Turkey.

In this great confrontation, the pre-eminence of power politics is blocking cooperation that is nevertheless essential on global issues as important as climate and sustainable development, high technology and artificial intelligence, social rights and, of course, peace and disarmament, particularly nuclear disarmament.

Against this backdrop of international brutality, the Middle East has even reached a peak of uninhibited violence and savagery. Using the terrorist attack by Hamas on 7 October 2023, which claimed around 1,200 lives (and 250 hostages), particularly civilians (which is an exceptionally serious act), as a pretext, Israel has embarked on a war whose objective is not to attack Hamas and its leadership, but the entire Palestinian people. The total number of victims of the Israeli war probably exceeds 100,000. In Gaza, 90% of infrastructure and services have been destroyed. The Israeli authorities are seeking the deportation or ethnic cleansing of the Palestinians. They want to finish the job started by the Nakba in 1948.

A genocidal process is underway. The intention is clear. International justice has taken up this highly criminal tragedy without France, its European partners and the United States really seeking to stop it, at the risk of being considered accomplices tomorrow. The appalling reality of failing to assist an entire people in danger is all too evident.

This paroxysm of political violence also has its roots in history, in colonisation and occupation. As Elias Sanbar (former Palestinian ambassador to UNESCO) so aptly explained, it is a case of one people being replaced by another through colonisation.

In this crime of historic proportions, Israel’s unacceptable impunity is guaranteed in particular because this state is a privileged strategic partner of Western powers, including France. Once again, it is the logic of power that dictates the law, in defiance of fundamental human values.

The end of the Cold War has thus ushered in an uncertain, complicated and dangerous era. All the political, social, economic and technological contradictions are taking on a strategic dimension, increasing the risk of confrontation. All these realities, combined with policies that kill diplomacy, point to a future of major insecurity and the possibility of major wars.

The arms race, including nuclear and high-tech weapons, is fuelled by the development of such a context. In 2024, global military spending reached a record high of $2.718 trillion.

Obviously, many new questions are being asked. I will choose two.

First question. With Trump, is NATO dead? In other words, is this the end of Atlanticism and the Western camp?

For Europeans and for US administrations following a traditional line, such as Biden’s, NATO is a political-military alliance based on common strategic and political needs and ideological requirements (Western values).

For Trump, this approach is no longer relevant. He sees NATO as a matter of opportunity and circumstance. It is therefore no longer a matter of principle or political necessity. It is a contingency.

In truth, it is difficult to know how Trump would behave in the event of a major crisis in Europe or Asia involving China, with the risk of a major war. Once the demands of values and principles fade away, strategic choices can vary according to circumstances and the interests of the United States, as defined by Trump himself. There are no longer any established principles, but above all choices based on opportunity.

It should also be noted that there is neither a complete break with previous policies nor unanimity in the United States on such an approach, including, it seems, within the Pentagon. According to experts and some media outlets, ‘total chaos’ reigns in the US Department of Defence.

Finally, NATO is not just a strategic alliance. It is also a framework and a means of hegemony and guaranteed profits for Washington and the US defence industry. Despite or with Trump, the death knell has not yet sounded for NATO. Moreover, the US administration has affirmed its desire to remain in NATO. And Trump will attend the NATO summit on 24 and 25 June in The Hague.

Second question. What does a war economy mean?

The war in Ukraine is cited as the main reason for a war economy in France and rearmament in Europe in the face of the Russian threat. We must also question (as I have already pointed out) what European leaders mean by the Russian threat. Moscow is suspected of wanting to launch military offensives against certain NATO member states. However, is it really that simple?

– In 2020, Russia was unable to play a major role in the Second Nagorno-Karabakh War. In this war, Turkey provided decisive support to Azerbaijan against Armenia. This was the main factor.

– In December 2024, in a complex regional context, Russia was unable to save the regime of Bashar al-Assad, its Syrian ally, which was swept away in a matter of days by an armed offensive led by the Islamist group Hayat Tahrir al-Cham, which emerged from the jihadist al-Nusra Front, itself a successor to al-Qaeda. For the most part, this happened without or against Moscow.

– Finally, during 2024, Russia was only able to conquer 0.66% of Ukrainian territory. This looks more like a stalemate than a conquest. In Ukraine, Russia has demonstrated from the outset of the war a lack of military power and global power.

We must therefore be more cautious and demanding in our assessment of the motives put forward to justify rearmament in Europe.

We must look for other explanations.

The United States wants to counter the rise of China, and has made this its priority. The Europeans would like to become players capable of influencing the balance of power in Europe, particularly in the war in Ukraine. Both sides are seeking to reaffirm their power, and the United States its supremacy. This requires a strategic reconfiguration.

Since Barack Obama, the United States has wanted to disengage from Europe in order to make the desired shift (the pivot) towards Asia and China. To make this possible, much greater military and financial investment is needed from the Europeans to compensate for the withdrawal of the United States from the European continent.

But this withdrawal seems more problematic than people are willing to admit. It must be understood that, for the United States, its military, strategic and political presence in Europe is an affirmation of power, with very significant military assets that give the United States political weight and the ability to intervene well beyond Europe: in the Middle East, the Mediterranean and Africa. The American presence in Europe therefore reflects the resources and interests of a global power. It is not so easy to break away from it… Moreover, withdrawals have been announced, but not a complete withdrawal.

The fact remains that security issues in Europe are systematically treated today as military issues, without ever raising the question of political and diplomatic solutions and options that would finally allow all actors, including Russia, to be included in the reconstruction of the conditions necessary for collective security in Europe.

The war economy, however, is not just a question of security. It is also an issue that affects the mode of development. According to the UN, we are currently witnessing a ‘global development crisis’… Planned military spending can only exacerbate this. In today’s world, a major contradiction is irrepressibly emerging between, on the one hand, a chosen path of power ambitions and ever-increasing military and technological demands, with the heavy economic and budgetary burdens that this entails, and, on the other hand, the resulting social and political consequences.

We must therefore ask ourselves: what kind of world do we want? What are our social demands? How can we build human security that is conducive to security and peace?

A few quick words in conclusion

Something strikes me today as a decisive element in the movement of the world, what some (Farid Zakaria, for example) call ‘the rise of the others’. The rise of the others, that is to say, the gradual and irrepressible historical affirmation of yesterday’s dominated peoples. This is not new. It is the affirmation of the global South, with the recent creation of the BRICS, which is beginning to put on the agenda, despite the high level of challenge, a process known as de-Westernisation, or even the questioning of the dollar. This will certainly be very difficult, but these themes express the need and the push for a real transformation of international relations. This reveals the urgent need for a response to the crisis of the capitalist mode of development and to global challenges.

Already, the spirit of de-Westernisation of the international order is expressed in the collective rejection by the countries of the global South (beyond their heterogeneity) of Western war policies (they are not enforcing sanctions against Russia), and the systematic practice of double standards, always to the detriment of the Palestinians. This is a very significant fracture in international relations.

It is certainly no coincidence that the UN is now so marginalised and stigmatised for its inability to solve problems. Yet what leads to powerlessness is, first and foremost, power itself, the logic of power and the illusion of force that goes with it. After the first Gulf War, the Western powers were unable to win any of the wars they waged. Global problems continue to worsen. The current trajectory of international relations demonstrates this on a daily basis. It is high time to think and act differently.

In 2025, we can mark the 80th anniversary of the creation of the UN by deciding to give it much greater importance in defining the necessary alternatives. We must bring the United Nations back into the public debate.

For many, current events and history show that war is an irremediable means of resolving conflicts. Clausewitz’s famous phrase is often quoted: war is the continuation of politics by other means. This formulation is highly debatable, as it tends to lock thinking into a cycle of wars and fragile periods of peace.

It is a seemingly banal statement, but it confines reflection to the premise that war is inevitable or an invariant of human nature. This is a fundamental error that we should no longer make. We must move away from this single-minded thinking based on the primacy of power and force in human relations and politics. It is true that war is a reality that is difficult to overcome. This is difficult to deny. We must therefore agree with Edgar Morin, who rightly observes that ‘humanity is struggling to become humanity’. This reminds us who the main actors are and who holds the key to the solutions: the peoples of the world and their societies. It is, in a way, a call to make peace, now more than ever, a major political and social struggle.

En savoir plus sur jacquesfath.international

Abonnez-vous pour recevoir les derniers articles par e-mail.